- Home

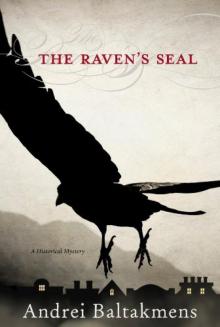

- Andrei Baltakmens

The Raven's Seal

The Raven's Seal Read online

A T O P F I V E M Y S T E R Y

Published by Top Five Books, LLC

521 Home Avenue, Oak Park, Illinois 60304

www.top-five-books.com

Copyright © 2012 by Andrei Baltakmens

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by information storage and retrieval system—except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews—without permission in writing from the publisher.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

eISBN: 978-0-9852787-6-2

Cover design by Megan Moulden

Book design by Top Five Books

Cover image courtesy of Getty Images

Illustration of Airenchester by Jeffery Mathison

With cities, it is as with dreams: everything imaginable can be dreamed, but even the most unexpected dream is a rebus that conceals a desire or, its reverse, a fear. Cities, like dreams, are made of desires and fears, even if the thread of their discourse is secret, their rules are absurd, their perspectives deceitful, and everything conceals something else.

—Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities

Contents

Book the First: Setting Snares

I. The Quality of Airenchester

II. A Call and a Challenge

III. A Play of Blades

IV. Captain Grimsborough Reports

V. Courtroom Scenes

Book the Second: The Eminence of the Bellstrom Gaol

VI. A New Mode of Society

VII. Refreshing Company

VIII. Introductions and Reports

IX. Humble Requests

X. Mr. Palliser’s Shadow

XI. Under the Sign of the Black Claw

Book the Third: Jackals and Lions

XII. Superior Lodgings

XIII. Means and Contrivances

XIV. Mister Ravenscraigh’s Interest

XV. Hours and Days

XVI. Detecting the Scent

XVII. On the Watch

XVIII. Closing In

XIX. Brought Down

XX. The Case Reversed

Book the Fourth: The Raven’s Seal

XXI. A Prison Fever

XXII. The Rogues’ Tribunal

XXIII. The Captain’s Sabre Goes to Work

XXIV. Execution

Epilogue

Author’s Note

About the Author

More from Top Five Books

BOOK THE FIRST

SETTING SNARES

CHAPTER I.

The Quality of Airenchester.

THE OLD BELLSTROM GAOL crouched above the fine city of Airenchester like a black spider on a heap of spoils. It presided over The Steps, a ramshackle pile of cramped yards and tenements teeming about rambling stairs, and glared across the River Pentlow towards Battens Hill, where the sombre courts and city halls stood. From Cracksheart Hill, the Bellstrom loomed on every prospect and was glimpsed at the end of every lane.

Yet one night (a very dark night, and fiercely cold) at the failing end of 1775, the Bellstrom Gaol was no more than a dim line on the hill, pierced by the glow of banked fires behind its barred windows and one gleam of candlelight in the top chamber of its highest tower.

Lady Stepney held a great entertainment at her place in town. Brilliant flambeaux flared on the cobbled drive. A row of carriages wound along the street, and the drivers sat, hunched on their high seats with their coat collars turned up, and took what cheer they could from the music and loud voices heard at the windows. The air was cold and hard and clear, like the fine lead crystal laid on the tables. Darkness gathered behind the riverside warehouses and about The Steps, but the quality of Airenchester moved in a finer medium, in the brilliance of countless flames.

Mayor Shorter attended, among many worthies. He stood before a snapping fire and gallantly took the hand of any man passing. Here were the masters of Airenchester: merchants, bankers, and magistrates, its grand families in cheerful concord, takers of punch and conversation. The quality talked and fanned themselves, joined the quadrille or sat at cards, chattering and laughing, passing, curtseying, and bowing. Yet it became a little hard to catch one’s breath in the press and stir of the crowd, and the hot flames of the candles were reflected in acres of plate silver, facets of crystal, gilded mirrors, brilliant threads on coats and gowns, and bright eyes. No one noticed that a little bird had slipped inside and become mazed among the chandeliers and painted arches, and desperately fluttered against a closed window.

Mr. Thaddeus Grainger might have seen the sparrow, if he had raised his eyes one more time, as if casting up among the heavens for some fantastic engine that would pluck him from the company. He stood in a corner, behind a knot of animation and laughter in which he took no part. Mr. Grainger was a young gentleman of a good height, well-featured, and dark. Though his coat and collar were a touch plain, he was finely dressed. He glanced up again, weary of what he found below. Indeed, there was something careless in his stance and expression. He had an excellent name (among the quality of Airenchester), a commendable fortune in property, scant ambition, a great deal of idleness, and perhaps too fine a sense of his failings and too much pride for his improvement.

He shrugged and stepped forward, but before he had gone far, Lady Stepney was before him.

“You are not escaping!” she exclaimed and rapped him with dire playfulness on the chest.

“Should I flee such fair captivity?” he asked, smiling lazily.

It was hard to make out much of Lady Stepney, besides an impression of lace and silky stuff, perfume and coiled hair (not much of it her own), dazzling jewels, and some small stretches of whitened flesh.

“You won’t charm me, young Grainger.” Her fan fell again, as Lady Stepney made a cut that would gratify a fencing master. “You must dance again with Miss Pears. I foretell a fine match there, a prosperous match. And I think I have yet to see you pass a civil word with anyone else.”

“They have passed enough words with me,” he retorted. “Throwsbury bores me with corn and some business concerning drainage, Grantham with hunting and dogs, and I have barely avoided Tinsdowne and a lecture on divinity.”

“You are a wicked man,” charged Lady Stepney.

“I plead innocence,” he cried, with a bow.

“Nonsense. I won’t hear you. Take another glass at least and join Mrs. Marshall. She is desperate for a partner at piquet.”

“Mrs. Marshall can find an abler opponent than me.”

The fan recoiled, and Grainger concealed a wince, but the mist of finery that constituted Lady Stepney did not relent.

“Mr. Grainger, when you get a wife, she will correct your negligent ways. We shall make you respectable.”

“You set this speculative wife a terrible task.”

“Ghastly man! Come in and speak to Miss Pears. She will be inconsolable if you pay her no more attention.”

“My regrets. It is very close. Some cool air will restore me.”

The fan made a sword-cut again and lighted on his shoulder. Grainger inclined his head minutely. “Young Massingham will attend this evening,” confided Lady Stepney. “He presents rather well. His mother lately remarried a baron, you know. I hear he has an eye for Miss Pears.”

“He is no rival of mine,” said Grainger coldly.

“Fie! You wear it too lightly.”

“I think you are as keen to make scandals as matches, my lady.”

>

The fan twirled and touched him on the chin. “Horrid man. You don’t know me at all. I shall let you go and think of you not one bit more.”

And with an airy turn and a lifting of the heels, Lady Stepney, gown, fan, jewels, and all, departed, leaving Thaddeus Grainger with his hand on his chin. For a moment he held this musing stance, and then, with a shake of his head, he too took his leave.

THADDEUS GRAINGER descended the stairs, hat and cloak in hand. Gusts of heat and music rolled down from the open doors, but the night air cooled him, and his eyes cleared. Another party, newly arrived, four or five gentlemen, came up with heavy footfalls and loud talk.

Mr. Grainger paused to let them pass and sketched a bow, a trifle unsteadily.

The first to approach him was Piers Massingham. He was a year or two younger than Grainger. Handsome, though with a narrow cast of features, he was of the same idle order: apt to his pleasure but acutely conscious of his position. He crossed before Grainger, who was forced to check his motion on the stairs.

“Pray, do not let me detain you,” said Massingham.

“Rest assured, I would by no means tarry on your account.”

“You are in haste,” noted Massingham, standing easily and toying with his gloves.

“Indeed, no,” rejoined Grainger, smiling thinly without a trace of pleasure.

“Mr. Grainger,” said Massingham loudly, “is set on an assignation, and we have thoughtlessly delayed him.”

A general snigger erupted from the three behind him.

“Not at all. I give you good night.”

“Of course. Kempe, don’t dither. Step aside and let Grainger pass.”

And so the one went down and the many came up; the one down into the sharp, still night, to pass the rows of carriages and along the road, the many up into the whirl and merriment, the rousing music and the staring lights.

MR. GRAINGER continued on foot, descending from Haught into Turling and the low town. Many carriages rolled abroad, as the best of Airenchester took their pleasure, for Lady Stepney’s was not the only place to call tonight. Link-boys scuttled through the streets with their lanterns to light the way for well-dressed gentlemen. Grainger’s mood improved as he got in among the scrawl of streets and dim courts clustered in genteel chaos nigh on the river and in the daylight shadow of the Cathedral spire.

He came into a small, dark square, where old-fashioned houses with steep roofs and carved gables leaned against each other. All was quiet. He searched about by the thin light of the half-moon and gathered up a handful of fragments of a shattered cobblestone. He stared up, counting audibly under his breath, until he found the one high window he sought. Then he took a stone in hand and lofted it against the glass.

The stone struck the pane and rattled away, but the noise did not disturb the repose of the square. Grainger selected another shard heavier than before, aimed, and loosed it at the same target.

He was testing a third missile when the little window opened a fraction.

“Who’s that?” cried a voice.

“William, are you asleep?”

“Not a bit. I happen to be standing at my window, conversing with a madman.”

Grainger hurled another pebble, which clattered against the wall. The window was thrown open, and the head of Mr. William Quillby appeared, almost filling the frame. Quillby was near on Grainger’s age, a clergyman’s son encumbered by education and no fortune. He was, by profession, a scribbler and taker of notes, and to this end a journalist who followed society and the courts. On occasion he intervened sensibly in fractious coffeehouse debates, in consequence of which he was known to quietly entertain Views not always to the credit of authority, and on one side or another of the latest cause he and Grainger had first marked their acquaintance. His good humour well matched Mr. Grainger’s restless moods. William had a mass of brown hair, perpetually disordered and now tousled by sleep; a broad, honest face; and guileless brown eyes. He wore his nightshirt.

“For God’s sake, stop that!” he hissed.

“Get up, William!”

Another flying stone clipped the frame.

“I am up! You’ll wake the whole house!” Mr. Quillby lodged in the compact top-room of a respectable (if limited) establishment.

“What?”

“I said you’ll wake the whole—no more stones, if you please!”

“I just wanted to see if you were awake.”

Mr. Quillby returned to the window and said resignedly: “Evidently I am. Evidently, I have no better way to spend my evenings but to wait on lunatics flinging masonry about.”

“Excellent fellow!” For the first time this night, his coolness and airy manner were discarded, and Grainger grinned up at the open window. “Let’s go out.”

“You have been out. To Lady Stepney’s, I assume.”

“I have been stifled and overheated; I have been condescended to; I have been courted and expected to pay court, in the name of good form; in short, I have been fatally bored—but I have not been out.”

“Are you drunk?” asked Quillby.

“No, no. Not in the least. I am merely a little short of the high mark of sobriety.”

“What time is it?” Mr. Quillby did not soften his suspicions.

“It is but midnight.”

“I thought it rang two.”

“So it did. William, come down, I implore you. You are the only worthy fellow in this town. The only fellow who is not a slave to good form.”

“I must turn in some work tomorrow. I have in mind a piece pointing out the most grievous abuses of the clothmakers—”

“Tomorrow, good! Work on it tomorrow. Admirable. Come down to the Saracen and tell me all.”

“I was asleep,” returned Mr. Quillby, becoming querulous.

“A good glass of Rhenish will settle you for writing,” declared Mr. Grainger. The last chip in his hand sprang at the casement.

“If you only stop that, I shall be down presently,” said Mr. Quillby, resigned.

“William, you are the best of friends,” said Grainger, clasping his empty hands behind his back.

CLUSTERED BELOW the sheer face of Cracksheart Hill, The Steps lay within sight of the Bellstrom Gaol. There was no straight path from The Steps to the gaol, though it seemed to command everything below, for at the highest point of that district were nothing but hard cliffs and weathered reaches of stony wall, reaching to the base of the castle.

A prisoner forlorn in the lowest cells might stare out through hard bars onto the top of The Steps and behold a tumbling, toppling pile of steep little roofs, missing and broken tiles and slates, crooked, narrow chimneys set all askew, and the winding, constricted stairs and pinched lanes that made up that quarter. But the eye could not see the noisome drains and fetid puddles, nor apprehend the stench of rags or smouldering coal fires, or the foul air of close human habitation. A mass of rickety hovels, slumping walls, makeshift doors, cracked and winding stairs leading one to another in no order, uneven yards, and scavenged lumber was The Steps.

Closer to the river than the gaol, at the top of a coiling set of crumbling stairs, lay Porlock Yard, a frozen, muddy square, four slumping walls of blind windows and descending moss. In one corner, close to the ground, stood a door somewhat stronger than most, and behind it a dark lodging-room. Not entirely dark: in a little stove the coals were burning down to feathers of ash, and their glimmerings fell upon the grate. On a chair by an uneven table sat the sturdy figure of a woman, dozing, with a bundle in her lap that could only be a small child wrapped against the chill. Underneath the table, indistinctly seen, were three or four small heaps of clothes and blankets, twitching and shifting occasionally, and in the farthest corner of the room, on a low bed, was another figure beneath a heap of covers.

A far bell chimed. There was little silence to be had in Porlock Yard. At all hours there could be heard heavy footfalls on the rattling stairs, the shuffle of bodies stretched on those same stairs, the groan of timbers, the

bellows of men and the shrieks of women, and the cries of children. The little room was uneasy with breathing. Another woman, more slender than the first, nodded and dozed on a three-legged stool by the stove. Every movement in the yard drew her out of rest.

The person on the low wooden bed coughed, stirred, muttered, coughed again, and turned all around. A dark head rose.

“Cassie, is he back yet?”

The younger woman drowsing on the stool shook herself. “No, Father.”

“Damn the boy. Where’s he gone?”

“I don’t know, Father.”

“I think you do.”

The girl did not reply. The bed creaked as the man shifted.

“Fetch a light, child.”

The girl rose, as softly as she could, and rummaged along a thin mantelpiece for a rushlight. She took it to the stove, leaning forward to open the grate. For a moment, the faint orange glow touched her face. It was a youthful face, though it had known want, weariness, and fear. The grey eyes were bright and clear; the line of brow and cheek strong, though haunted now by thought. From under the shawl some strands of the lightest brown hair escaped, which caught, by the dying embers, stray touches of red and gold.

She fired the wick from the ashes and brought it back to the table. The heavy figure in the deep chair was roused, raised herself, and the child in her lap mouthed a complaint. The woman’s face was thickened by age and veined and coarsened by labour and harsh wear. It had been handsome once, and the hair, with more red in it than her daughter’s, was threaded with strands of white.

“What is it?” said the woman. “Is he back?”

“Not back,” replied her daughter.

The stronger glow revealed also the head of her father, propped on one hand and an elbow, above a mass of worn covers and clean rags. The head was shaggy, seamed, and weathered. Along one side gleamed an old scar, got from a bayonet.

“You know where he’s gone. The boy tells you everything,” accused Silas Redruth.

“I’m sure I don’t.”

The Raven's Seal

The Raven's Seal